Mentorship Anecdotes

(Check out the related photo gallery at the bottom of the page)

05/04/2024

It’s early May in the Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. I’m sitting on the ridge of a mountain called Excelsior, a mellow prominence in a vast setting of snowy peaks and massive alpine cliff faces. A single dark cliff band, about a hundred feet high, runs through the middle of the mountain and tapers out at its edges where it meets the ridge. The ridgeline curves around a full ninety degrees on each side of the mountain creating a half bowl. I’m sitting on a rock patch with a group of people I met that morning at the trailhead parking lot just 4 miles away, but that was hours and many ridgelines ago, and I feel remote. Two of the guys who have nonverbally decided that they are the leaders of the group are joking with each other about doing heroin.

Carefull! Says the bearded one, Your going to corrupt young Julian! He points at me. The other one laughs. I’ve just turned 20, and comments directed at me like this have been on the increase for the past year. Almost exactly a year before, I started working on a Hotshot crew and was the youngest by two years. The next oldest was a 21 year old named Pablo, a white skinned, blonde haired, strongly built kid from Reno, Nevada. He had also started on the crew when he was 19 and it was recognized that you were going to take some shit for being that young.

The last of the group reaches our snack spot and we sit for a few more minutes to let her take a break. There’s seven of us in the group that day. Six of us are sitting in our little circle, refueling after the first pitch of the mountain – one of them is a firefighter named Pat who splits his time between living in Tahoe and working for the San Francisco Fire Department. His girlfriend, Brita, who I know nothing about except that she’s been thinking about trying ice climbing (she told me in a brief conversation on the way in) is sitting across from him. There’s a girl named Sammy, who is the slowest of the group, a ski guide named Steven, who I’ve met before when I interned at a guiding company he works for, and the bearded one named Joel, who is acting like my chaperone on the trip, much as I dislike it and feel he has little more backcountry skiing experience than me. And then there’s Chris and me. Chris is across the bowl, sprinting uphill to get his second lap of the day while we are taking a rest on the way up for our first. Chris is my neighbor and I’ve gone into the mountains with him a few times before. Sometimes we rock or ice climb together, and occasionally we go skiing, although those occasions are less frequent since I’m usually traveling for ski competitions or training. I love the technical side of mountain travel, but I’m also trying to become a professional skier, so that usually takes priority. Chris is the opposite. He did a few ski competitions in the late 90’s, but mostly he runs and ice climbs. He’s spent a good amount of time climbing in the Alaska Range and various other rugged mountain ranges around the world, so I trust him. Another, older, mentoree of his told me once that he climbed Mount Huntington in Alaska, a peak renowned in the climbing world for its difficulty and seriousness. I also asked him on the drive down from our neighborhood in Truckee whether he has climbed in South America. He said yes, he has climbed Cotopaxi. Chris is a man of few words, and I got no further detail. He once ranted about the Everest climbing business and about the disaster that killed the team of Rob Hall, Scott Fischer, and all of their clients except Jon Krakauer who he told me walked down to his tent at high camp while the disaster happened and essentially took a nap while a world class climber and guide, Anatoli Boukreev, climbed and descended the mountain over and over trying to save the group, but inevitably just did body retrieval. Krakauer then published an article in Outside Magazine (which was later expanded into the book Into Thin Air) which blamed Anatoli for the incident. When Anatoli tried to publish a rebuttal in Outside, he was denied (leading to the book The Climb, Anatoli’s version of the incident). It was extremely rare to get this type of detail and outward passion from Chris. When we went into the mountains together, we usually worked in silence. I’m typically soft spoken, and when I wasn’t out of breath from trying to keep up with him and tried to ask a question or comment on something, he would often yell “what?!” So I talked less around him at first. Chris was either starting to like me more or I was learning to speak louder around him because He hadn’t yelled “what” at me in some months. He was also helping me plan a road trip through the Cascades at that time, and I think he might have found some respect for me in the fact that I was committing a lot of time and effort into climbing mountains, something that maybe he didn’t see before.

As soon as the first person started picking up their gear from our rest, I put my pack on with my skis strapped diagonally to the back, and boot packed up the rest of the ridge ahead of the group. I summited, and waited five minutes before I saw Joel coming over the false summit a hundred feet away. Pat and Brita followed another five minutes later and said that something had gotten into Steven so he and Sammy had dropped in early. Brita had left her skis on the false summit to get on the way down, but we decided to drop in at a different spot so Joel ran down and grabbed her skis for her.

“Thank you!” she said. To me, having been taught a lot of my mountain travel skills by Chris, the hardo, and having spent a season on a Hotshot crew, this act of service seemed ridiculous to me. It reminded me of a scene in a book I had read by the legendary climber Joe Tasker, Savage Arena. Joe and his partner Pete, were somewhere high on a mountain in the Himalaya and Pete asked a small favor of Joe and Joe snapped back at him saying I suppose you’d like me to spoon your dinner into your mouth as well, or some similarly ridiculous statement. The act seemed uncharacteristic of a typical unguided mountain group dynamic.

We finished the day a few hours later and all drove to the town of Mammoth for burritos. Joel brought up going to the local hot springs and Chris was adamantly against the idea.

“I love hot tubs and hotsprings, but I hate the type of people that use them”, he said.

“What are you talking about?” said Joel, “we use hot springs”. Chris starts listing off times he’s had bad experiences at hot springs, like when he was threatened with a gun. After dinner we go back to our cars to drive to the hot springs and I go with Chris back to his truck.

“I’m just going to text Alissa [Chris’s friend who he ice climbs with] where we’re going. She’s on her way down to ski tomorrow”. I sat in silence in Chris’s passenger seat for the next thirty minutes while he sent a text every once in a while and stubbornly avoided going to the hot springs. Without a word, Chris turned the truck on and started driving.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“Back North”, he said, “the skiing will be good on the South and East faces of Dunderberg”. There’s a storm coming in the day after tomorrow so we’re expecting a windy day with firm snow, hence Chris’s strategy to ski what gets the most sun.

I asked Chris in the camper that night whether it made sense to get up at the same time we had that morning. We had woken up at 5 AM and sat around until 7, driven to the trailhead to meet everyone, and then slowly gotten ready and left the trailhead just after 8. I was in the habit of getting up early, but not for no reason, and I would have appreciated some extra sleep after climbing almost 8,000 feet that day.

“No, we can get up at six”, he said. I turned the lights out and Chris played soft rock on a portable speaker for another half hour until I asked him to turn it off because I couldn’t sleep.

I woke up the next morning and brought our boots and gloves in from the truck to warm up. We sat around for a while and I ate the rest of the strawberry pancakes and a cold, pre cooked breakfast sausage that I had shoved into a tupperware a couple days ago. Chris drives us to a small pullout just before the trailhead parking lot where we get our gear together and put our ski boots on. We take off across a field of dirt and firm snow on a slight hill until the mountain juts up 2500’ in front of us. I decided to slow my pace to leave myself strength for another lap while my legs were already sore from the day before. I noticed half way up that Chris isn’t as far ahead as he usually is. I accredited it to the fact that I hadn't gone out with him much since my time on the hotshot crew, so I’d probably gotten better at hiking. Chris tops out maybe five minutes before me and I meet him on the summit. He is sitting on a rock looking out over the landscape. Mono Lake is sparkling down below and I think about how good that water would feel on my skin right now. I sit down and have some of the trail mix I made.

“You need to move faster when you’re climbing the volcanoes on your road trip, said Chris. I wasn’t even pushing it that hard up that, that’s the speed you need to be moving. Practice it next lap.”

What, is this a Hotshot crew? I thought. I’m getting yelled at for not hiking fast enough! Even on the hotshot crew I was actually a decent hiker. One day on a deployment to the Six Rivers National Forest we had decided to hike up a huge “dozer line” for the hell of it. We had started by prepping the dozer line from the top down, about a mile and a half, by having the two modules of the crew leapfrog each other as we caught up to where the other mod had started cutting. The superintendent met us at the bottom in his new Ram 4500, decked out with fire gear. We all got some water and a snack and put our packs on to pile into the back of the truck.

“Who wants to go for a hike?” Said Ron, one of the squad bosses. A couple people said they did, which meant that everyone had to go, culturally at least. I put my pack on and shouldered my chainsaw.

“You’re hiking?” asked a guy we called Two Bags who had been swamping (moving what I cut away from the fire line) for me that day. His nickname came from the two bags of IV he got earlier that season from pushing too hard and getting Rhabdomyolysis, a condition where your muscles start to break down into your bloodstream. We weren’t usually a saw team, but I had been doing well that season and was being rewarded with time running saw, something I loved to do.

“Yeah, you don’t have to come though”, I said. I knew that he didn’t want to hike, but if I went he would be forced to go with me, culturally.

“Don’t come, you’re good.”

“If you’re doing it I’ll go”. Only two people ended up not doing the hike, and Pablo shouted derogatory things at them as they drove off in the bed of the pickup truck.

We hiked half way and met up with a fire road where I suspected we might get picked up in the truck. I watched Ron in the front of the line to see whether he was going to stop on the road but he didn’t. We kept going on the dozer line up a particularly steep pitch and the person in front of me, a 33 year old we called CP, started slipping and falling out of line. I put an arm out and forced him up the hill. He was breathing hard and stumbling and I knew he wouldn’t be able to recover from this. The squad boss behind me got out of line and yelled at CP to keep up but he couldn’t. I pushed CP up the hill a little longer before the squad boss told me to pass CP and close the gap in front of me. I jogged for a few seconds and the rest of the line followed. This was called being slinkied: when someone in front of you creates a gap which makes you have to move even faster to catch up. It sucks. Cory kept up though. He wasn’t always the strongest on the crew, but we were good friends and I had chosen him to be my swamper, so I knew he was trying extra hard to prove himself.

“This is the shit that I like! You don't have to be here!” yelled Ron.

Five minutes later Two Bags started to fall out and Justin, a second year swamper, noticed and walked past the line to grab the dolmar off of Two Bags’ shoulder. Justin got back in line with two tools and dolmars on his shoulder and kept up. He ran marathons and was by far the fastest runner on the crew and a good hiker too. Two Bags didn’t recover and quickly fell out. I knew he was going to be pissed. He had fallen out before and he knew this was his chance to redeem himself from his past weakness. I felt sorry for him. We reached the last few hundred feet of the hike where the dirt turned to a mess of small boulders that went up at an extreme angle. Justin dumped the extra tool and dolmar off of his shoulder at the bottom of the pitch.

“Somebody else take this fucking thing.”

“I got it!” I said as loud as I could while breathing hard, and grabbed the dolmar as I passed by it. I finished the hike with the dolmar and a chainsaw on my shoulder in addition to our 28 pound line gear. The superintendent and A mod captain were waiting at the top, looking down at us.

“Goddamn Little John!” Said the superintendent as I huffed past him and set my gear down at the top.

“Justin carried it most of the way”, I said. I don’t know if they heard me, but Justin didn’t say anything either. It was widely known that he was quitting firefighting at the end of the year, so he was fine letting me have the credit. The difference between that and the bootpack I had just done up Dunderberg was that Chris had spent the last thirty five years of his life running ultramarathons and hiking in the mountains everyday. No matter what, I didn’t stand a chance against him.

We put our skis on and skied down a wide chute on the right side of the face. Fifteen minutes of skiing later, we reached the bottom.

“Want to do the other line I was talking about?” He said.

“Yeah, sure”, I said. I had started making a conscious effort to say yes to more of the things Chris suggested, even though they often ended up with me suffering. We pushed across the flats and got back in the truck and drove to the trailhead parking lot – a closer starting point for our next line which was a sliver of snow between two loose looking rock ribs. We fast walked across the flats again and Chris stopped at the bottom where the snow started.

“Will you get my helmet off my pack?” he said, “I’ll get yours”. I pulled the helmet off of his bag and then took my pack off to get my own. Chris was concerned that there would be rockfall in the chute so he was having us wear helmets on the boot up. There were two people about a third of the way up the chute.

“A good way to get fit in the mountains is to try to catch people”, he said. I started off at Chris’s pace, but he was back to his usual half running instead of pacing me so I quickly fell out.

I caught up to the people in front of us at the choke of the chute, about halfway up.

“Your friend’s off like a rocket!” said the man as I passed him. He was Australian and wore a safari hat.

“I know”, I said. I looked up and could see someone else topping out at the top of the snow patch. It didn’t look far so I pushed a little harder. Chris reached the top five minutes later and I kept pushing as the finish looked closer and closer. The rocks around me were radiating heat, and I started to get heat tingles, something I had only experienced before when working on the hotshot crew. I topped out, completely out of breath and my legs about to give out under me. Chris stared at me as I walked the last few feet and set my pack down next to him. He turned away from me and continued a conversation he had been having with a young woman who told him she was from Driggs, Idaho. I ate my trail mix and sipped water in silence.

“Let me get some nuts”, said Chris. “I haven’t eaten”. I handed him the bag and he took a handful. The girl’s boyfriend walked down from the summit just above us and started talking to Chris. He asked where he was from and Chris gave his usual answer: “Mass”, but clarified that we lived in Tahoe. We got our gear on and skied down the first pitch. I heard the boyfriend say “Oh yeah he’s from the East Coast, look at those turns!” We came to a small section of rock that Chris carefully stepped over on his skis and I jumped over past him, landing on the next snow patch.

“That would’ve been the way to go”, said Chris. No matter how much Chris dominated me in every other aspect of the mountains, I was better at skiing down hill than he was. The rest of the chute was deep spring corn snow, and I reconveined with Chris down below the choke.

“That was really good”, I said. Chris agreed.

“You see all this debris?” he said, pointing to the snow chunder in the middle of the chute. “It’s all fallen off these cliffs around us. Like that”, he pointed to a patch of snow thirty feet up on one of the cliff walls. “You can see the rocks that have fallen from the cliffs too, like that dark spot down there in the snow. It came from the cliffs. That’s why I stayed out of the middle of the chute on the way up, I don’t know if you noticed that”.

“Yeah, I did”, I said. I had thought that the chunder was from an old wet slide, but Chris knew best. We got back to the truck and Chris set up the camper for us to change in and get ready for the drive back home.

“We timed that well”, he said. This might have been a complement to us as a team by Chris’s standards. Chris drove us back and we had a good conversation about long boarding and different types of mountain races. After four years of knowing each other, I was starting to be convinced that Chris actually enjoyed my company.

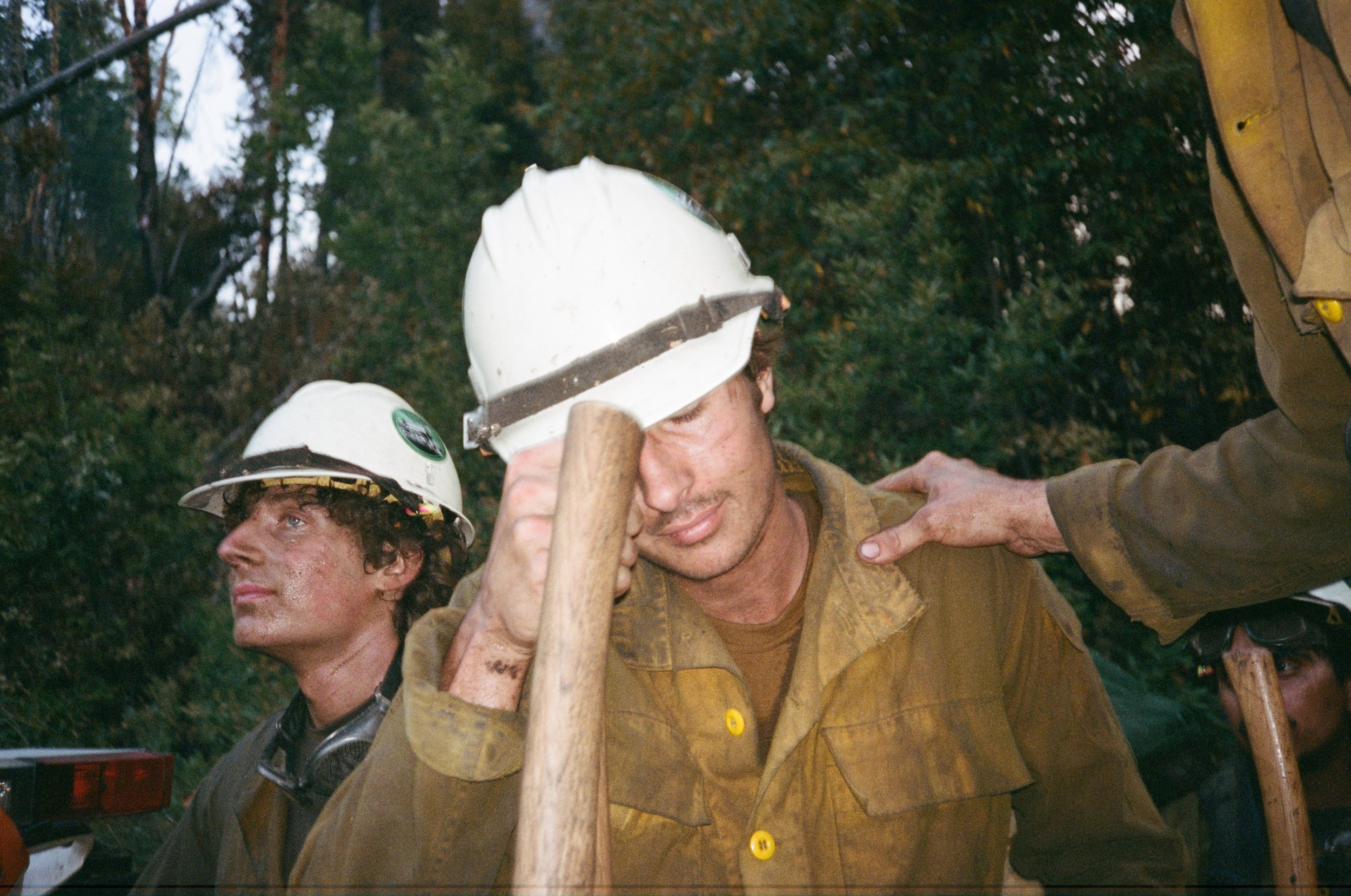

Two hotshot captains on the left and a lead firefighter and sawyer on the right sitting on a logging pile in the deep woods of far northern British Columbia, Canada. Weeks of working in the rain and mud and dealing with Canadian politics was taking it's toll.

A tough shift, apparently.

Chris with Excelsior Mountain in the background on the left

Lunch break on a prescribed burn operation. A low point for mental health.

My tracks next to Chris's coming down Excelsior

Pat, the firefighter, skinning back from Excelsior (seen in the background)

My saw partner spraying out the remnants of a spot fire. We had spent the past couple hours cutting and digging in smoke so thick that we were dry heaving and had to take turns bumping out to cleaner air.

A crew member stoked on the delivery of burrito's while on a burn operation.